Just two-and-a-half months prior to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Niko Rukavina got married and now has an eight-month-old child at home. On top of that, he became the interim head coach of the men’s volleyball team this past fall.

“I would say it was a rollercoaster,” said Rukavina. “Handling the highs of the rollercoaster, but also the downs and the low points. I think that’s been a challenge, but also an exciting part of coaching.”

The pandemic greatly impacted the way teams went about day-to-day life. Social gathering limits made it impossible for entire teams to train at once; contact tracing made it challenging for athletes to access the facilities they once frequented; and the effect the pandemic has had on mental health is yet to be fully understood.

According to a 2021 survey from Statistics Canada, 25 per cent of Canadians 18 and older screened positive for having symptoms of depression, anxiety or post traumatic stress disorder as a result of the pandemic. This number was up from 21 per cent earlier in the pandemic in fall 2020.

While student athletes have been at the forefront of the return to sports at Ryerson, Rams coaches have also been impacted greatly by the pandemic.

They had the tall task of acting as leaders in their community, guiding athletes through unprecedented times and facilitating a positive experience for their players. Throughout the last two years, coaches did everything in their power to try and make the next sporting season the best one yet, even if it was in jeopardy.

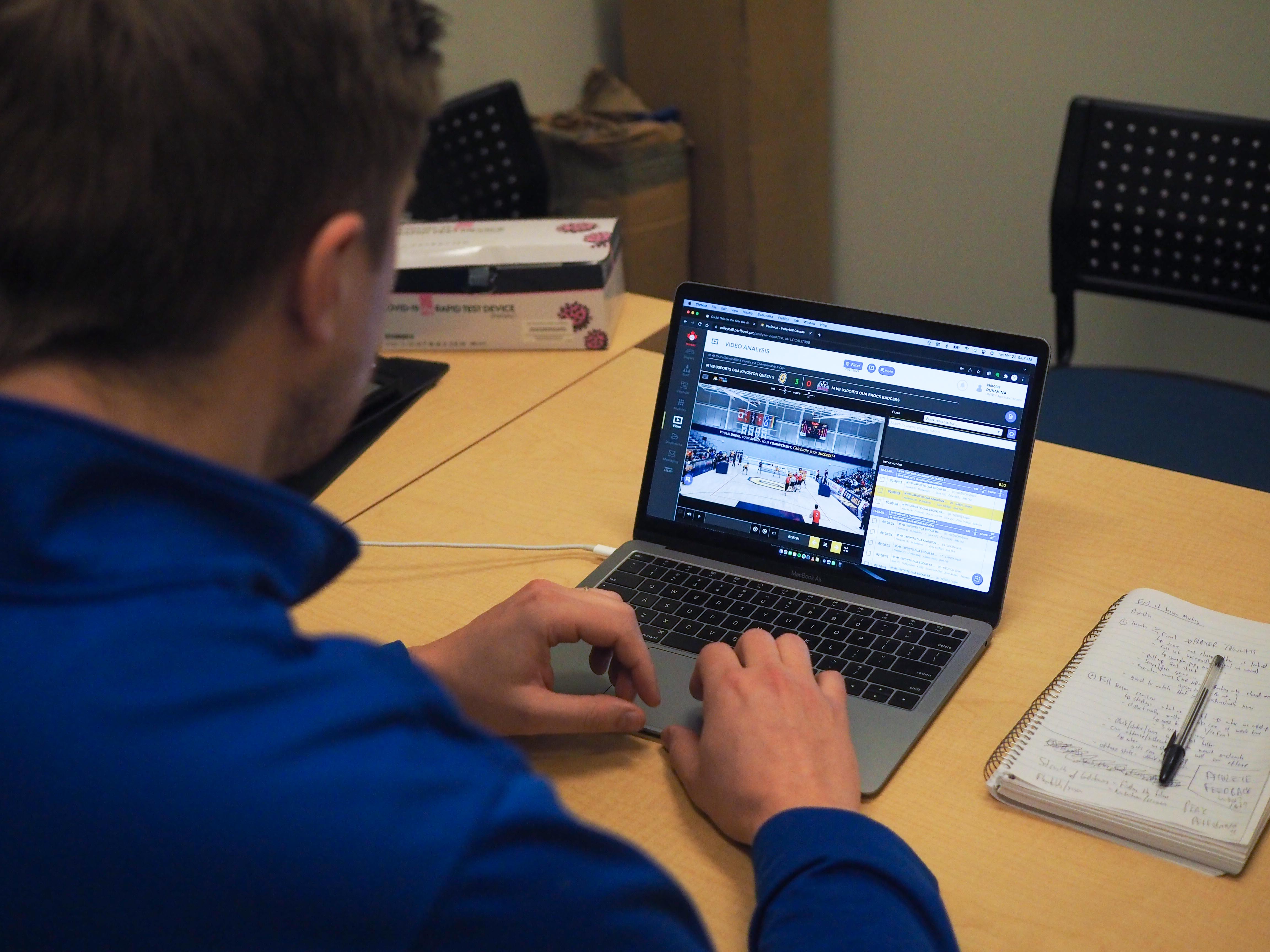

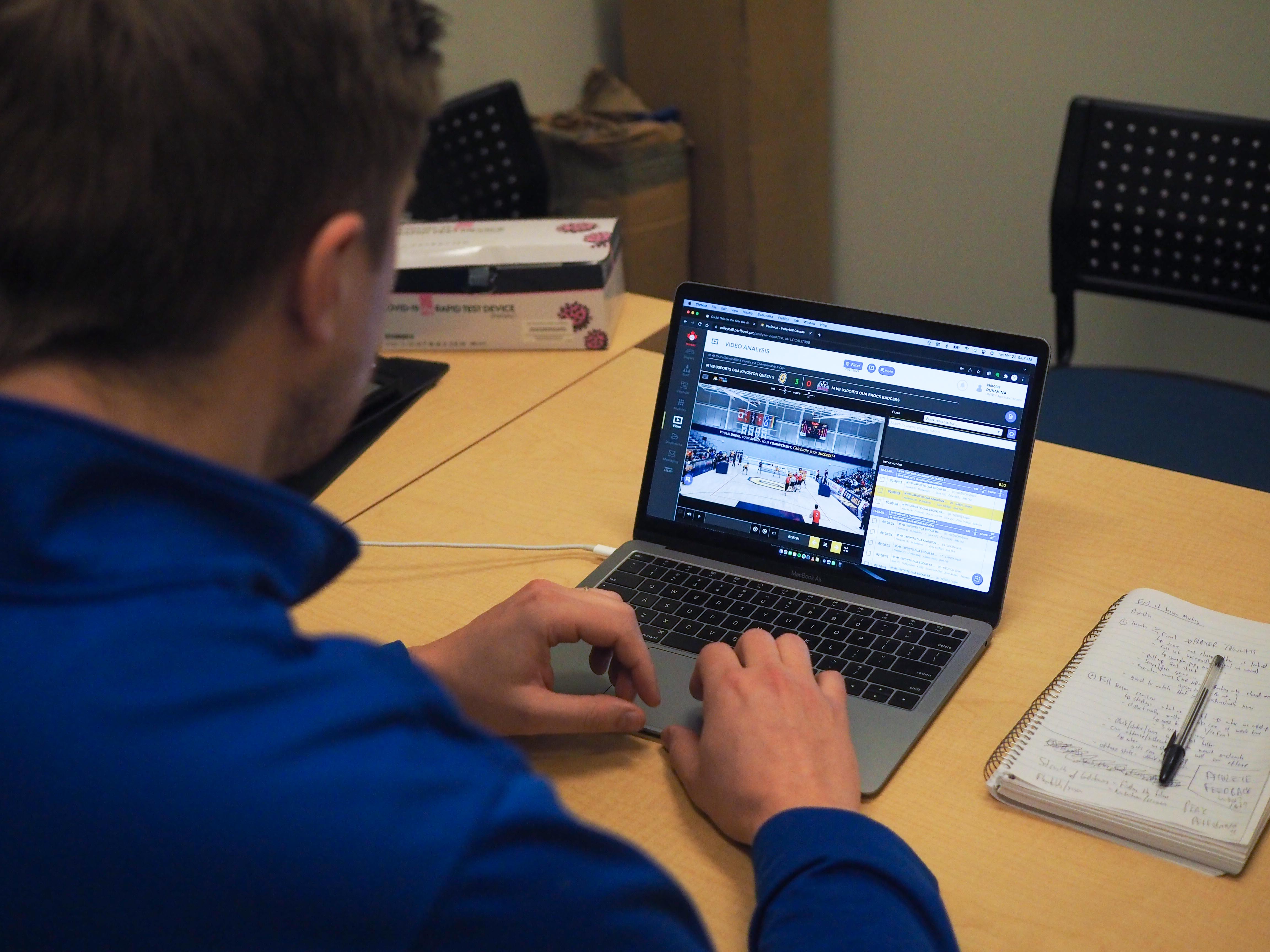

Rukavina knew the 2021-22 season wouldn’t come without difficulties. He and his staff did their best to create bonds with their players that would hopefully translate to the hardwood once games started.

“Obviously everybody got a lot better at doing things on Zoom,” he said. “To not be able to be face-to-face, let alone be on the court together, was very difficult.”

Rukavina said mental health is a top priority for any program he’s a part of. He stayed in constant communication with his team; whether it was simple check-ins on their mental wellbeing or talking volleyball,he reiterated they weren’t alone and that there would be positive takeaways once the pandemic was over.

Rukavina described a team building activity he did with the team to share some laughs during lockdown. He challenged his players to a virtual game of ‘keep up’ where each player had to send a video of them keeping a volleyball up for as long as they could. Rukavina said the exercise brought the team together and gave them something to laugh about.

“We were just grateful to be on the court, grateful to be playing a game [and] grateful for the opportunity,” he said.

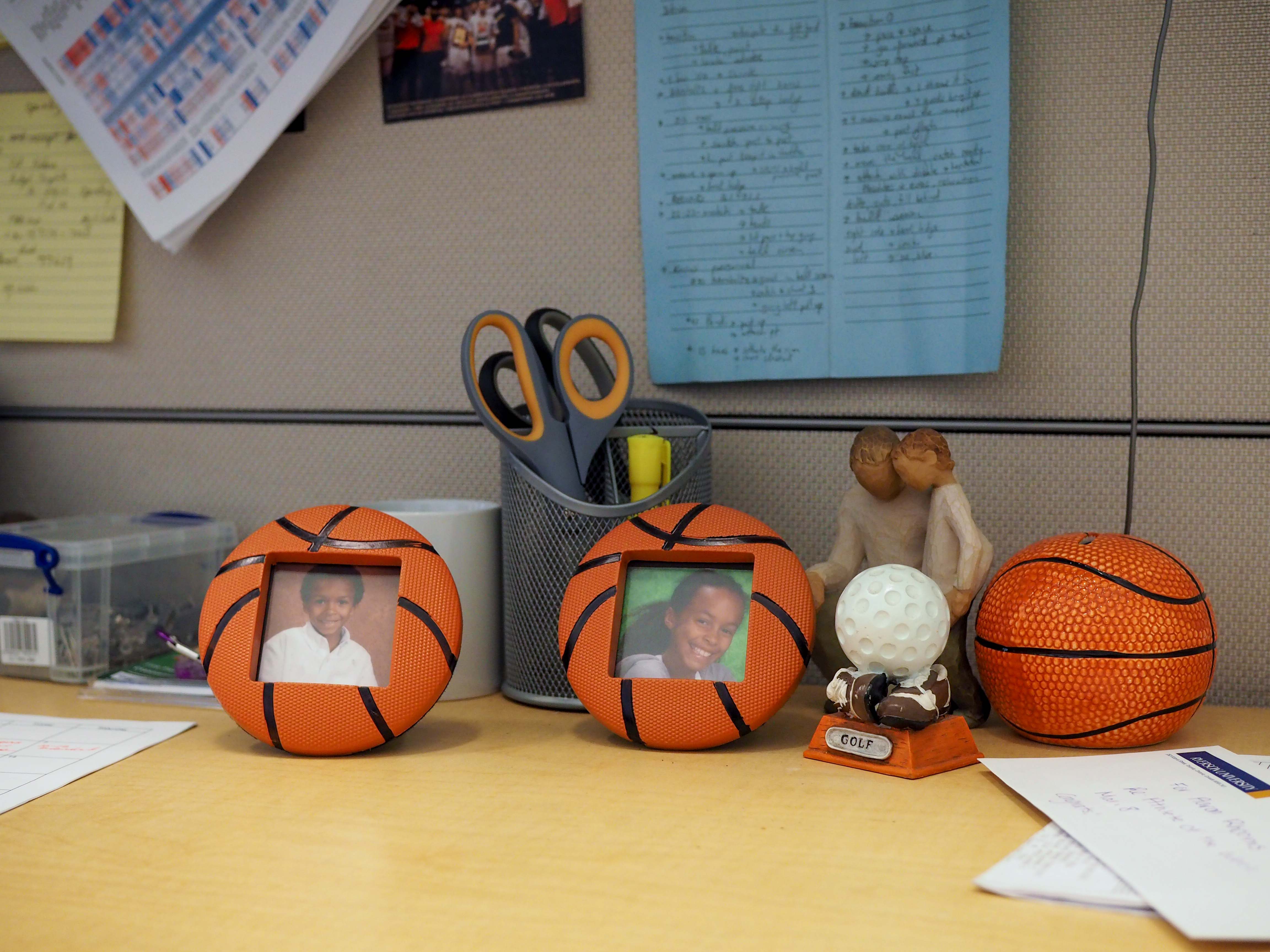

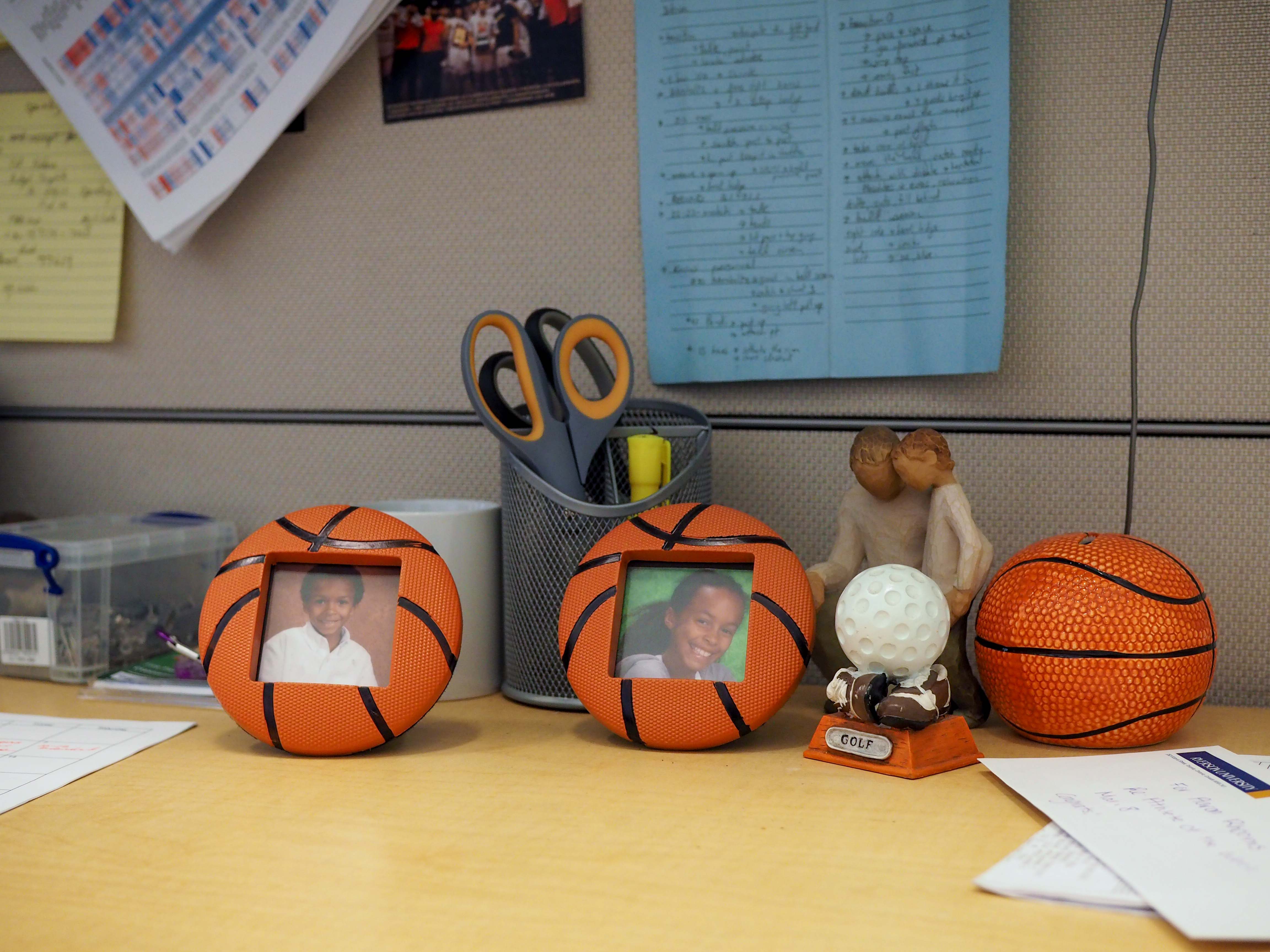

Nobody knew what was in store when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, but for Rams men’s basketball coach David DeAveiro, he knew he had to get his son home. At the time, DeAveiro’s son was playing in a basketball tournament in the U.S., so his main concern was getting him back to Ottawa where they could be together.

“We were just grateful to be on the court, grateful to be playing a game [and] grateful for the opportunity”

DeAveiro was then hired as head coach of the Rams men’s basketball team in April 2020, one month into the start of the pandemic. Once it became clear that the 2020-21 season wouldn’t happen, his new goal was to provide his athletes with outlets to be successful and make sense of the world around them.

“We would bring in guest speakers who would talk to our kids, especially about what was going on with the George Floyd situation,” said DeAveiro. “[We brought in] more Black speakers, identified role models for some of our kids, listened to their stories and their tales about things that they went through and things that they’re doing now to be successful.”

DeAveiro accepted that it would be challenging to create strong relationships with athletes that he had never coached, but that didn’t stop him from doing everything he could for his players. He focused on helping his players get to where they wanted to get to, had candid conversations with them about what their future plans were and tried to help them find jobs and opportunities to play professionally overseas.

Coaches don’t only have families at home; they also have a family in the gym, training room and on the court that they need to take care of. This added stress took its toll on DeAveiro, but he continued prioritizing the mental health of himself and his team.

“I think the other thing is that this was hard on everybody. We’ve talked to the athletes about what the athletes have gone through, but nobody really talks about the coaches,” he said. “This was hard on coaches too.”

DeAveiro said the most recent COVID-19 restrictions in December 2021 that prevented the team from playing were the hardest on him. He saw himself starting to fall victim to depression, so to combat it, he travelled back to the U.S. to be with his son who plays for the basketball team at Valparaiso University —just to be around the sport he loved so much.

“With the pandemic, it allowed a lot of people to spend more time with their family. So I got to spend more time with my family, my children, especially those who are a little bit older doing their own thing,” he said. “My son was in college, my daughter is in university, so it just allowed me more time with them that I wouldn’t normally have.”

Jason Saker worked from home during the first year of the pandemic. It was early 2021 when the opportunity to be Ryerson’s fastpitch coach arose, and he jumped at it. Saker said he had always wanted to coach at the university level and being able to do so for his alma mater was a vision come to life.

“I love saying that I graduated from Ryerson, so if there was an opportunity to give back in any aspect, this was definitely one way that I feel I was able to contribute.”

But taking on the role of coach in the midst of a pandemic was no easy feat. Like many coaches, Saker wanted the season to be about the players and he did everything he could to establish that from the get-go.

This included interviewing graduating players and any returning players to get their opinions on the upcoming season and how he could make it a great experience for them.

“We’ve talked to the athletes about what the athletes have gone through, but nobody really talks about the coaches”

“For me, it’s never about the wins and the losses, although it’s always better to be on the winning side than not, but I wanted to let them know that I was there to support them in any way possible,” he said.

Saker knew the 2021 season would be different from those in the past, and he did his best to navigate his team through the new challenges. In a normal fastpitch season, the team makes overnight road trips to face programs all over the province. But with COVID-19 restrictions in place, the team wasn’t able to stay in hotels, making travelling and competing that much more difficult.

Nonetheless, Saker said he was happy with the way the season went, and happy for his players that they were able to compete in the sport they love after so much time away.

When you see Rams coaches in action, they’re probably hollering at players on the court or leading them with fiery intensity. But, behind the scenes, their role is much greater. The pandemic pushed them to be humans first and coaches second, offering their guidance and support in uncertain times.

“It’s never about the wins and the losses, although it’s always better to be on the winning side than not, but I wanted to let them know that I was there to support them in any way possible”

“I think the pandemic gave us a sense of assessment and reflection that we don’t always get, especially in the middle of the season,” said Rukavina. “For myself as a coach I took that as an advantage and a positive, and I’m really happy with some of the relationships that I’ve formed in those times.”

Whether it was through games of virtual ‘keep-up,’ long chats on Zoom or offering professional mental health support and resources, Rams coaches did it all over the last two years for their players: their second family.

“We were just grateful to be on the court, grateful to be playing a game [and] grateful for the opportunity”

“We’ve talked to the athletes about what the athletes have gone through, but nobody really talks about the coaches”

“It’s never about the wins and the losses, although it’s always better to be on the winning side than not, but I wanted to let them know that I was there to support them in any way possible”