Just before the midseason break, first-year defender Saije Catcheway walked into the Mattamy Athletic Centre dressing rooms with her teammates hours before a game. There, she and her teammates looked around the room, their eyes catching sight of their new jerseys hanging in their stalls.

Catcheway’s last name was embroidered on the back, with only a capital “R” outline in blue adorned on the front; the brand new jerseys were the first of the team’s road design that didn’t include the name “Ryerson” like the old ones did. It’s a moment that Catcheway can’t get out of her head.

Now, she’s waiting for the real changes to be made.

Ryerson University’s name change has been one of the most contentious issues on campus since it was announced in August 2021. Conversations about funding, timing and potential new names have been discussed on a nation-wide level for almost a year, with a short list of names promised by the University Renaming Advisory Committee by the end of the winter 2022 semester.

Indigenous students on campus say news of this name change has been particularly important, but like all Indigenous issues, the range of opinions about the decisions is diverse; some students are excited about the name change, while others think it’s an unnecessary change to the school’s identity. The impact of the switch has reached all facets of the school—including the Rams, who are one of the most branded organizations within the university.

On June 3, 2021, the Rams women’s basketball program was the first varsity team to independently drop the name “Ryerson” from their team. Other varsity clubs followed suit, two months before Ryerson’s official announcement of a name change on Aug. 26.

Ryerson Athletics also released a statement on June 9 supporting athletes in their decision to independently drop the university’s name from team monikers. By the 2021-22 Ontario University Athletics (OUA) season, all Rams varsity teams were donning redesigned jerseys that didn’t include the school’s namesake.

Richard Norman, a postdoctoral fellow at the Ted Rogers School of Business Management through the Future of Sport Lab at Ryerson, says creating change in sport is about creating more diverse spaces. He says this includes addressing norms and practices that are attached to violence, like offensive mascots, traditions and namesakes like Egerton Ryerson. It’s important for teams to interrogate what the legacy of their team is, he explains.

“I think it's really important that you say ‘all right, the connection with this name is it is creating emotional responses and traumatic responses from people,’” Norman says. “And if we don't honor that, then what is our role as [we are] continuing this colonial project and on the mechanisms that are there, are we really allowing that conversation to shift, to change and actually to make space for the peoples that have been oppressed for such a long period of time?”

But Indigenous athletes on the Rams say getting new jerseys isn't the only progress they want to see. For them, changing their name should be the first step on the road to progress for the school’s relationship with Indigenous students and communities.

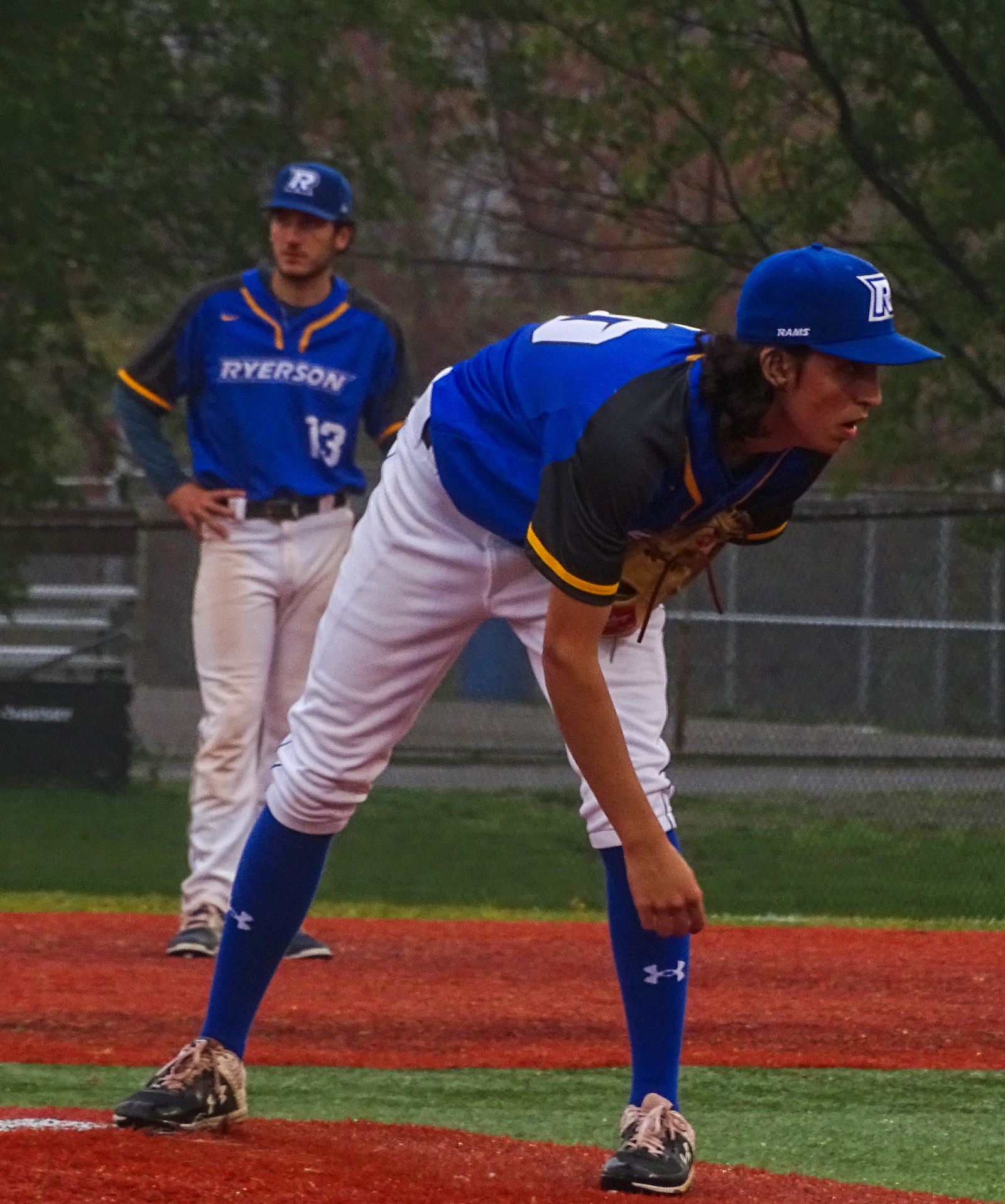

Gus Cousins remembers getting into the sport of baseball as a kid. He recalls seeing photos of himself celebrating a first or second birthday at a Toronto Blue Jays game with his parents.

“I have a feeling that probably kickstarted it at a very young age,” he jokes.

Twelve years ago, at the age of nine, Cousins started playing baseball competitively. Before coming to Ryerson, he played several seasons for the East York Bulldogs and was excited to start playing at the university level.

Cousins was born and raised in Toronto; his father is Indigenous and his family's band is Carry The Kettle, of the Nakoda Nation. He says while the name change is necessary for the institution, there are more pressing issues the school could be diverting funds to.

“Last year, my band’s reserve out in Saskatchewan went through a whole boil advisory,” says Cousins. A boil water advisory is a recommendation by local health officials to use boiled or bottled water when a community’s drinking water has been contaminated.

He worries that with the school investing so much time and money into the rebrand, people might be getting away from the issue at hand; the mistreatment of Indigenous communities in Canada.

He says Indigenous Peoples in Canada are still facing unfair conditions. According to the Government of Canada, there are still 34 long term drinking water advisories across 29 communities. Since the beginning of 2022, three new advisories have been added.

In 2021, the Borgen Project reported that 33 per cent of off-reserve First Nations and Metis are food insecure, as are 54 per cent of people living on Indigenous reserves. COVID-19 remains a threat to Indigenous populations as well, with, the CBC reporting rising case number in Indigenous communities around Canada, and a lack of health-care professionals was cited as a cause for spread.

In 2017, The Eye reported that the cost of a name change could cost “millions of dollars.” For Cousins, he’d rather see that money go towards improving living conditions for Indigenous communities.

“I just think those are what impact people more immediately than changing the name right away.”

“It's hard to say conscious efforts are being made because there really isn't much we can do,”

Norman says athletics dropping the Ryerson moniker from its teams and the name change of the school as a whole should be a launch point in making athletic spaces more inclusive, but not the end. He explains that understanding the intention of the name change and being able to recognize the violence attached to Ryerson’s namesake, is where progress will start. Norman says it’s important to understand how the name is creating emotional and traumatic responses to people.

Not acknowledging the harm the namesake caused prohibits the conversation from shifting and changing to make space for people who have been oppressed within sport and society for such long periods of time, he adds.

Part of the reckoning will mean diversifying all facets of sport, including coaches and referees. “Having that representation is an important recognition of our visual expression, so that people can see themselves in these places. ”

When she was ten years old, Catcheway started playing hockey in a boys league, in her hometown of Winnipeg. She remembers how much her dad loved the game and skating, so being on a team was a big deal for her family.

But it wasn’t on this team that she found her love for the sport. Her favourite time of the season was in the springtime, usually right after play ended, because that’s when she and other Indigenous hockey players would come together for tournaments.

“We call them native tournaments,” she says. “They're Indigenous hockey tournaments where you put together a team of Indigenous athletes and you have a tournament for a weekend.”

For Catcheway, whose family is Skownan First Nation, these tournaments are where some of her fondest memories of the game come from. It was at one of these tournaments that her team became the first mainly-women squad to win the championship at the Indigenous tournament.

Being an Indigenous woman playing hockey in the OUA, she knows she’s a role model for young athletes. For her, being on the team is about much more than her own progression as an athlete.

“I don't see it as it [just] propelling me forward,” she says, “But me going forward, I know is setting an example for the younger generation in my community.”

To Catcheway, the name change is about more than just an institutional rebrand; it's a symbol for change in Canada.

“The running water, the boil water advisory, the health care systems, the [Child and Family Services] systems, all of that for Indigenous people … are ongoing issues that really are only taking time because they're not a priority,” she says.

Catcheway says sometimes it’s difficult to feel progress from the name change, especially when it feels like it's unfolded so slowly, but she’s been appreciative of the support from her team.

“It's hard to say conscious efforts are being made because there really isn't much we can do,” she says. “ I really respect that [the team is] still on board, even with the unknown of it all.”

She says the name change should happen, not necessarily just for the sake of rebranding, but because it’s proof that people outside of the Indigenous community are able to recognize that change is necessary.

“There have been conversations about it and seeing people who aren't Indigenous make some points about it, I think it's just very foreign [to me] and I like to see it.”

On Orange Shirt Day, the team took a photo in their jerseys and didn’t include the Ryerson moniker. She says small actions like that make her feel like bigger change is possible.

“It doesn't have to be grand actions or anything like that. But I think just little thoughts and people being conscious of it is where change is going to happen,” she says. “So it's been really cool this season and sort of being a part of it.

For her, it’s about being supported by people who aren’t directly facing the impacts of Ryerson’s history.

“The whole reason for it is a lot more meaningful than just a name change.”